When looking at new (and used) car prices, you will probably have noticed that electric cars are more expensive than an equivalent gasoline car: sometimes much more expensive. A good example of this is the Hyundai Kona SE, with the gas version retailing at £18,200.00 in the UK ($19,990 in America), whilst the Kona Electric SE will be £27,250.00 in the UK (which would be around $34,650 if the Kona EV sells in America). A massive price difference for essentially the same car.

Why are EVs more expensive?

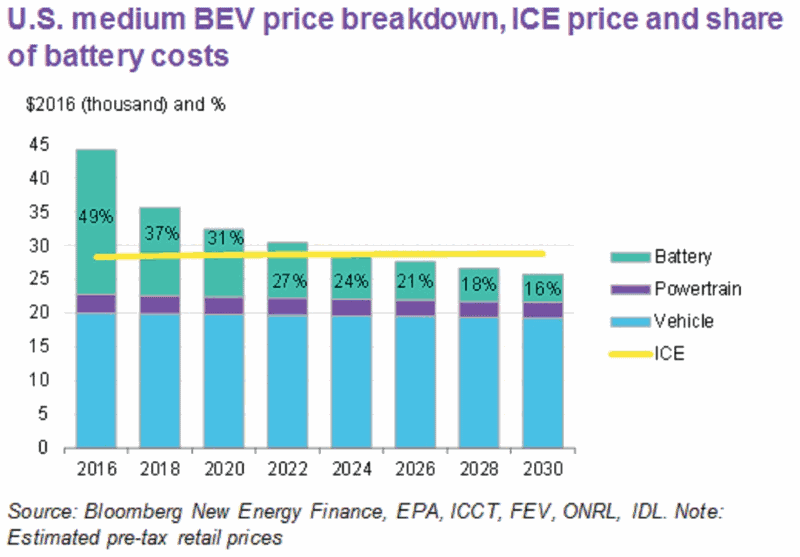

As seen in our ‘are there budget EVs for the working class?’ article, the battery pack is responsible for up to half the price of an electric car:

…the average EV sale price in May 2018 was $36,539, compared to an average of $20,528 for a gasoline-powered compact car. This is due to the sheer cost of the battery pack that goes into an EV: currently around $205 per kWh. What this means in practical terms is that the cost of the battery pack in a Chevy Bolt EV is $15,734.29 at list price (more when delivery is taken into account)! This is close to half the overall MSRP of $36,620.

This logically makes sense – there’s already massive amounts of infrastructure and equipment for internal combustion engines, but comparatively little for large-scale Lithium-ion batteries. Industry and manufacturers need to scale up building of these high capacity battery packs for electric cars before their prices can really fall.

Will battery prices fall?

The question of whether they’ll fall is naturally the real question. Whilst no-one can predict the future, thankfully a range of industry experts believe that they well.

Morgan Stanley (the American investment and research company) predicted in February 2018 that lithium prices (naturally one of the main material of an electric car’s Lithium-ion battery pack) will fall by 45% by 2021. This would help reduce the overall cost of batteries, which is measured by $dollar per kWh of capacity provided. The current price for batteries is over $200/kWh, however Morgan Stanley predict this will fall below $150/kWh by 2021 at the latest.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance also predict that this could drop to as low as $70/kWh by 2030 – a massive, game-changing drop from the $200+/kWh that all car manufacturers (other than Tesla) currently pay. Infact, it is predicted that 2024-2025 will become an inflection point whereby electric cars are cheaper than gasoline cars!

Finally, on the note of Tesla: many people call them a battery company not an EV company because of their sometimes ground-breaking research on battery technology. And when EVs first started being introduced in 2010, the battery price was estimated to be as high as $1,000/kWh. In 2018, Tesla are now looking at just $190/kWh for the Model 3 – and this (downward) trend is set to continue.

So the short answer is that based on current information and research, electric car’s battery packs will become cheaper. And since they’re such a big part of the overall EV price, this will bring down the EV price considerably.

Will increased EV demand block battery price falls?

Right now EVs – despite enjoying good sales growth – still haven’t hit mass market adoption in the majority of countries. When they do, and there’s an even bigger surge in electric car demand, will this cause battery prices to rise again?

The short answer is that there’s no way to know for sure, but that the research (above) has taken this into account where possible and they still think that battery prices/kWh are on a downwards trajectory. Certainly, Norway and China (who have enjoyed brilliant EV adoption recently) haven’t seen any issues with battery prices increasing as demand increases for electric cars

But what exactly are the main issues – in theory – with increased battery demand? Well, the main cost centres of a Lithium-ion battery pack are:

- Cost of equipment

- Cost of raw materials that make up the battery cells

- Staff wages

- Process costs

When demand for batteries increases, economies of scale (bulk buying, efficiencies being found etc) will lead to equipment and process costs falling. The question, then, is what about raw material – and staff – costs?

Staff costs (per battery produced) will theoretically fall as output increases, due to efficiency savings being found and shared knowledge increasing. At this point, 3 out of 4 main cost components will benefit from economies of scale – so this is a pretty good indication that the overall prices will fall – as research is already predicting.

However material costs are a harder one to gauge. We know that lithium prices should fall, but some of the other main elements in a battery – nickel, cobalt and manganese – are not due to fall in the same way. So these prices could rise as demand for EVs (hence EV battery packs) rise. This is where chemists come in though – the ratios of these metals can be altered, for example away from cobalt (one of the most expensive components per weight in a battery) to other cheaper alternatives. Also solid-state batteries may not need cobalt at all.

So in short: 3/4 main cost components of batteries should fall as demand rises, whilst the last one (materials) is trickier – but overall, the $/kWh of electric car batteries should fall even as demand increases.

$5,700-$7,100 cost savings per EV

In addition to the battery packs, research firm McKinsey have investigated exactly how electric cars are produced by numerous car manufacturers, and identified up to $7,100 of cost savings per electric car produced. Their research concluded that these cost savings can be achieved “by the early to mid-2020s”, i.e. within the next half-decade. This would naturally bring the price of EVs much closer to gasoline cars. Some of the ways that they say these cost savings can be achieved are:

- Developing dedicated EV platforms (like VW are currently working on), which will allow EVs to be produced in a much more efficient manner.

- Simplifying EV designs (inside and out) so that they deliver what’s required, whilst also eliminating unnecessary switches, cockpit options and wiring which are more suited to gasoline cars.

- Optimize for urban driving: most people drive within towns and cities, for example for trips or commuting to/from work. Equally many electric cars either seem to offer too little range (with less than 100 miles/161 km) or too much range (such as luxury EVs with 300+ miles/483 km). Developing electric cars which have a range more tailored to driver’s expected journeys can lead to lower EV prices.

- Manufacturer partnerships whilst the industry transitions towards green cars: co-ops between companies such as Renault and Nissan (leading to the Zoe and Leaf electric cars) has saved both companies money compared to if they separately developed their cars. Such partnerships can help save other car manufacturers money, too.

The car industry is very competitive: meaning that the more money that electric car producers save per car, the more they will reduce the price for customers like you and I.

To conclude

As this article has explored quite a bit, the main driver of high electric car prices at the moment is their battery pack. But this should almost certainly fall steadily over the next decade, to the point where EVs are cheaper than gasoline cars. McKinsey’s research also shows that other parts of EVs will also fall in price, further reducing EV prices.

The below graph from Bloomberg New Energy Finance highlights this perfectly: